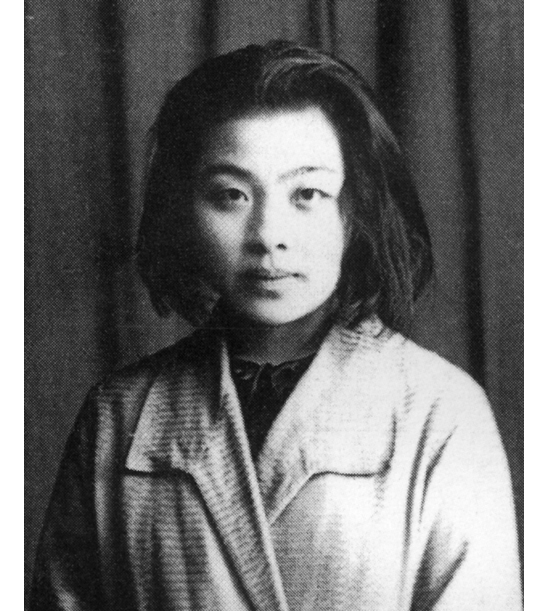

“Ding Ling” (c. 1930s), via Wikimedia Commons

The works of Chinese author Ding Ling are profound in their literary style as well as their political poignancy. As the author that gave a voice to the women of the May Fourth era, Ding forged new spaces for conversation on the complexity and status of the female subject by elevating feminist and socialist values in her works. Her complicated career, which ranged over fifty years, passed in phases deeply impacted by the political climate and context during which she wrote. During each phase, she remained a deeply controversial figure. Ding’s incendiary social and political presence can be explained in two ways: her specific brand of feminism and her personal navigation of the contradictions between Party and female subjectivity. Her feminism was one that demanded class analysis, putting her at odds with most of the feminist discourse coming out of the West. What drew more attention and controversy to Ding at home, however, was the way in which she embodied and wrote two different, new concepts of the female subject—the “New Woman” (xin niixing) and the “Modern Girl” (modeng gou’er). These two subjectivities, as I will later discuss, are irreconcilable identities that have deep implications for modernity and nationhood. Ding herself, I argue, personified the tensions between New Woman and Modern Girl, and through her writing and political activism questioned the ways in which State and Party demanded that she flatten her ideologies and personhood to fit cleanly within a single, legible identity: the model socialist woman. This paper seeks to trace the trajectory of Ding’s work through the different stages of her career, as well as unpack the multiple contradictions within which she existed: feminist and socialist, writer and comrade, and New Woman and Modern Girl.

Ding’s early works dwelled on themes of the complicated nature of sex, romance, and fulfillment for newly liberated female subject. Her writing became more explicitly political and critical in her middle years. During her activity within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that began in 1932, she wrote passionately to promote socialist ideals while also critiquing the unsatisfactory role of women within the Party. This, combined with what some critics found to be self-indulgent, bourgeois writing, led to Ding’s expulsion from the Party and exile to the countryside for over ten years. Her works from after she returned can be read as a reification of her commitments to socialist principles, as well as a new manifestation of her feminist beliefs. It is through these key stages that I will explore the contents of Ding’s feminism as well as the contradictions within her own subjectivity.

Ding emerged and developed her early thought during a period fraught with uncertainty and change. Growing up during May Fourth Movement (1917-1921), Ding was preoccupied with questions of liberation, nationalism, and new culture. Because a previous generation of feminists and reformers had already begun to address the most egregious forms of female oppression (the “Three Obediences” of Confucianism), Ding’s feminism can be classified as a “second-generation” feminism—one that was concerned with “the dilemmas of young women who had broken away from traditional social structures and conventional modes of behavior and had found themselves living on the fringes of society, up against the hostile world on their own.”, It is in this moment that the new female subjects—New Woman and Modern Girl—emerge in literary criticism. In “Miss Sophia’s Diary,” Ding focuses on the dilemmas and contradictions forced upon a Modern Girl. Her feminist concerns that come through in “Miss Sophia’s Diary” are centered around sexuality, love, and subjectivity.

Before analyzing “Miss. Sophia’s Diary” any further, it is important to discuss the identities of New Woman and Modern Girl. These identities manifested in relation to the widespread social and political developments of the time. As Sarah Stevens argues in her examination of these figures, “Chinese intellectuals used the ‘woman question’ as a keyhole through which to address issues of modernity and the nation.” In many ways, this was simply a way for male thinkers to replace an old set of social constructs with a new one under the guise of female liberation.

The New Woman can be understood as a positive manifestation of modernity with women as dedicated vessels of the state. At this moment, Chinese intellectuals were calling for a complete transformation of society—one which necessitated an abandonment of traditional, conservative, and bourgeois values. This transformation was enacted on the bodies and identities of women in the New Culture era. A good, moral New Woman was nationalistic, progressive, and educated. While constructed in the Republican era, the ideals of the New Woman would be translated into socialist terms during the Mao era. In contrast, the Modern Girl represented the negative aspects of the modern project. The archetype of Modern Girl was a platform on which writers and critics could express their anxieties and disillusionment with the promises and results of a total transformation of society. Described as “elusive, fragmented, and cosmopolitan,” the Modern Girl is similar to the New Woman in many respects—her education, location within urban settings, independence—but is set apart by her uncertainty in her own voice, subjectivity, and personhood.

Many of the contradictions within these identities are inherent to modernity itself. However, due to the moral and sexual components of the female identity, this tension became intensely gendered in the Chinese context. For instance, a New Woman might be praised for her careful attention to health, hygiene, and family in order find meaningful relationships and produce quality offspring that will continue the glorious national project of remaking a better China. The Modern Girl, however, comes under criticism for exploring sex, romance, or personal pleasure because she is too individualistic and self-concerned. Without the structures of traditional society, urban women who do not follow the guidance of nationalism and progressive politics may be led astray by such frivolity.

Sophia, the protagonist of one of Ding’s most famous short stories, is an example of such a Modern Girl. In this short story, Ding “address[es] a category of womanhood that was not victorious or revolutionary, but reduced, regretful, self-absorbed, self-pitying, and privatized.” Sophia struggles with the tensions of her lonely existence even though she is surrounded by attentive friends and admirers. As a frequently bedridden tuberculosis patient, she journals obsessively her thoughts and feelings that she dares not to share with others. Her illicit sexual fantasies about Ling Jishi, a handsome man with an underwhelming personality, drive her to anger and madness. She hates herself for not being bold enough to seize the object of her desire but feels disgust at the very thought of being intimate with such “a cheap, ordinary soul.”

Sophia can be ill-tempered, manipulative, and cruel to the people around her. A literary critic of the time described her as “selfish, emotional, frustrated, depressed, obsessive, lost in a mystical delirium, and pursuing bodily pleasures in order to forget her anxiety.” Despite the fact that she knows she is wrong, ultimately, she cannot stop herself from indulging these intense passions. At one point, she highlights her inadequacies in terms of her relationship to the ideal New Woman. In a moment of deep mental conflict and anguish, she languishes in her self-pity, which causes even more self-hatred, and writes:

When they are feeling bad, talented women these days can write poems about “how depressed I am,” “Oh, the tragic sufferings of my heart,” and so on. I am not gifted that way. . . . I should make myself good with either a pen or a gun even if its purpose is just my own vanity or to win the praise of some shallow audience. I’ve lowered myself into a dominion of suffering worse than death. All for that man’s soft hair and red lips . . .

Here, Ding explicitly draws out the misery and conflict caused by the ideal of the New Woman and the reality of the Modern Girl. Sophia theoretically possesses modern freedoms and independence but has found herself trapped in an entirely new set of limiting social conventions and structures. While she understands what a good, moral New Woman should do, she is obsessed with exploring and understanding her own subjectivity—an obsession which further tortures her desire to conform.

It is clear that Ding is sympathetic and attentive to the Modern Girl’s plight. She critiques the New Woman construction—one, I must reiterate, that was largely forged by male academics and imposed onto the broad category “woman” in order to further social transformation—through another set of characters in Sophia’s life. Yufang and Yunlin, two of Sophia’s closest friends, who assist her and take care of her, are a romantic couple who both appear to be model members of the new society. Despite being educated and progressive individuals, they are still deeply concerned with morality and purity. This is exemplified when the couple decides to move into the same apartment, but almost immediately go back to living separately because “they can’t trust themselves to make ‘good’ decisions when they’re in bed together, the best solution is to remove sexual temptations completely.” When Sophia “scoff[s] at their asceticism” they are not embarrassed, but “proud of their purity.” This comical example of the extremes to which the New Woman must go to maintain her morality despite her supposed liberation underscores Ding’s critique of the post-May Fourth society where figures like Sophia are tortured by the contradictions that the female subject must still endure. These themes would only build significance for Ding over the course of her career. In addition, her works took on a more explicit political tone where she brought class analysis to her feminist thought. I shall explore this shift through Ding’s short story “When I Was in Xia Village.”

Written in 1940, thirteen years after “Miss Sophia’s Diary,” “When I Was in Xia Village” reflects Ding’s frustrations and attitudes towards the CCP. These attitudes were informed by her close activity within the Party beginning in 1932. It is important to note that any sort of discussion or critique of the Party at the time was not just about the CCP, but extended to class struggle in general. This sort of metonymy was deliberately cultivated by the CCP in order to place itself as the exclusive vessel through which class struggle could be waged and won. Ultimately, debates over the composition and structure of the CCP were actually debates about what the revolution should look like and who it should serve. Ding’s thorough understanding of this reality drives her commentary in “When I Was in Xia Village.” Her dissent, which would later be used as evidence of her “Big Rightist” tendencies during the Cultural Revolution, did not come from a lack of commitment to Chinese socialism. Ding considers the “problem of futurity and normativity, or what women can expect to become if they commit themselves as a gender to the revolutionary future,” not any fundamental values of communism or feminism, in her critique. Her vision of feminism was theoretically upheld by the CCP. Ever since its founding, the Party has maintained explicit language on the equality of women and men and necessity of feminism for a successful people’s revolution. In practice, however, this was certainly not the case. “When I was in Xia Village” represents Ding’s observations and criticism of the treatment of women within the Party.

In “When I was in Xia Village,” the unnamed female narrator, a member of the Political Department of the CCP, is sent to recover from illness in the countryside. There, she becomes caught up in the local drama that has the entire village gossiping: Zhenzhen, a young member of the narrator’s host family, has returned to the village after being abducted by Japanese invading forces. Over her year of captivity, Zhenzhen was sexually abused, raped, and forced into marriage by Japanese soldiers. Later, it is revealed that Zhenzhen was being used as a spy for the CCP during her time as a Japanese prisoner and that she contracted venereal diseases from her rapists. Villagers reacted to this news with various attitudes ranging from disgust to pity. One villager tells the narrator “It’s said that she has slept with at least a hundred men. Humph! I’ve heard that she even became the wife of a Japanese officer. Such a shameful woman should not be allowed to return.” Another person claims that “now she is worse than a prostitute.” One of her relatives comments that “when she talks about those devils, she shows no more emotion that if she were talking about an ordinary meal at home. She’s only eighteen, but she has no sense of embarrassment at all.”

Every comment and judgement that the villagers made about Zhenzhen reveals the highly gendered and deeply problematic tension between “political loyalty and . . . sexual chastity” within the Party and society. Ding’s protagonist is a dedicated servant to the Party but also a social pariah. Her devotion to China’s struggle against the Japanese could have made her into a model New Woman and hero in the Village. However, despite her sacrifices, she is shamed and ostracized. Zhenzhen comments to the narrator that the villagers treat her so poorly because “they [are] proud about never having been raped.”

Still, Zhenzhen does not think of herself as a pathetic or wretched individual. As one author states, she “seeks neither their sympathy nor appears to care about their disdain.” She is proud of her actions, telling the narrator that “as I watched the Jap devils suffer defeat in battle and the guerrillas take action on all sides as a result of the tricks I was playing, I felt better by the day.” Further, she feels hopeful for her future. At the end of the story, Zhenzhen receives word from the CCP that she can go to Yan’an to get treated for her disease. After she is cured, she plans to attend school and start a new life far from the judgement of Xia Village. Here, Ding comes back to the question of futurity. If the Party does not prioritize the care and rehabilitation of people like Zhenzhen, they are doomed to lives of social isolation and ailment. The misogynistic society that has yet to be fully transformed will not be kind to those who are deemed impure, even if it is for the sake of Communism. To Ding, the Party had not done their due diligence in this respect. As Tani Barlow says, Ding is claiming that “the Party state is beholden to women’s future and must ensure that its own language is properly used, is placed in the hands of those whom it will benefit.”

While Ding’s fiction was compelling in form and style, with layers of symbolism and craft unattainable in nonfiction, her essay “Thoughts on March 8” is arguably one of the most impactful works in her canon. Published in 1942, “Thoughts on March 8” is an explicit work of feminist critique on the hypocritical treatment of women in the CCP. March 8, International Women’s Day, seemed liked the perfect, dramatic moment to express her thought. A key feature of her argument is the belief that “the construction of ‘woman’ in political terms had to come before any Chinese woman of any class would be liberated” and that “‘Woman’ is a social and political category just as ‘proletariat’ is.”

This distinction lays at the crux of feminist-socialist tension. In this essay—which was called a work of “narrow feminism” from members of the Party—Ding refuses to cede her identity and politics of woman to that of worker. In other words, the fate of women cannot simply follow behind the fate of the proletariat until communism is fully realized. “Thoughts on March 8” specifically crystalized this stance, and in doing so inspired mass criticism and struggle. Ding was forced to recant many of her positions in her public self-criticism. Even though she had to apologize for her strong indictment of the CCP, her words could not be erased. Barlow argues in her preface to the translation of the essay that “Ding Ling’s criticisms in ‘Thoughts on March 8’ played a part in reforming women’s policy and thus, indirectly, in Maoism’s victory.”

While the entirety of the essay addresses the unresolved contradictions that define Ding’s socialist feminism, certain parts of her polemic address the continuing themes of her fiction works, especially the woman subject’s place under Communism. Ding explicitly attacks the perfect New Woman subject who is totally devoted to the Party and nation:

I myself am a woman, and I therefore understand the failings of women better than others. But I also have a deeper understanding of what they suffer. Women are incapable of transcending the age they live in, of being perfect, or of being hard as steel. They are incapable of resisting all the temptations of society or all the silent oppression they suffer here in Yan’an. They each have their own past written in blood and tears.

In this passage, Ding claims authority to speak not only for herself, but for women as a whole. In doing so, she demands acknowledgement of the identity “woman,” as well as a recognition of the multifaceted and complicated subjectivity that is “woman.” The women that Ding describes possess some of the irrational and conflicted tendencies of Sophia as well as the strength and patriotism of Zhenzhen. She subverts and demystifies both oppressive archetypes of New Woman and Modern Girl.

Ding’s sharp writing drew the attention of Mao Zedong himself. In May of 1942, Mao gave “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Arts.” These talks which aimed to “ensure that literature and art fit well into the whole revolutionary machine as a component part, that they operate as powerful weapons for uniting and educating the people and for attacking and destroying the enemy, and that they help the people fight the enemy with one heart and one mind” are said to be partially a rebuttal to Ding’s works. In these talks, Mao affirmed the role of literature and art to be “to serve the masses of the people.” He railed against the bourgeois tendencies still present in literature that did not uphold Marxism-Leninism or the education and guidance of the masses. These standards for literary and artistic expression would carry enormous gravity for the remainder of Mao’s lifetime. It is by these very standards that Ding would be judged by in 1957 when she was accused of “Big Rightism.”

The charges that were levied against Ding represent the two struggles that I have been attempting to draw out throughout this paper: the tensions of feminism and communism and the way in which Ding embodied the contradictory identities of New Woman and Modern Girl. In addition, the idea of “anachronism” played a large role in the arguments against Ding and merits its own discussion and exploration.

At the basis of the theory of anachronism are the materialist concerns integral to Marxism. To Party members, Ding’s characters and writings were not only not the best representations of the political moment from which they were born, they were false representations. Despite the fictive nature of Ding’s short stories, the content of her literature had real political and historical power. Due to this power, the CCP believed that authors must be committed to extolling the truths of the contemporary glorious of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary moment. Ding was decried as a rightist whose works did nothing to educate or inspire the masses. Rather, they did the opposite. A critic of the time expressed anxiety over the fact that Ding’s Sophia was “not just a literary but a real historical player” who, in his words, “lacked all reason, had no spiritual life and had no principles.” Barlow writes that “the notion of anachronism can be a policing mechanism” because its “aesthetic presumes that history will condition and restrict the shapes that concrete women take.” Under this framework, Ding is charged with consistently and exclusively writing a perfectly accurate depiction of a universal woman. Her “crime of anachronism stems from the incapacity of the signifier women to ever completely be exhaustive because no matter how capacious it is, it can never contain everyone.”

Here, Ding’s predicament is the most salient: she cannot reconcile her feminism—which both decries the existence of a perfect contemporary woman and refuses to yield to class struggle—with her socialist beliefs in a way that is satisfactory to the Party. Neither can she herself exist as a complicated female subject. She has strong Marxist and nationalist convictions and clearly has played her part in advancing the modern project, but she also celebrates and values her own contradictions. She yearns to write and explore and answer questions on who and what a woman is and looks like in a moment of total transformation.

Ding was sent to the countryside for twelve years during the Cultural Revolution for her “rightist” tendencies. She was “rehabilitated” into society in 1976 where she continued to write, though her works showed a major shift. First drafted during Ding’s exile, her final novella Du Wanxiang was rewritten and published after her rehabilitation. It portrays, in the style of her early work, a single female subject. However, the subject she portrays is vastly different than characters like Sophia or Zhenzhen. Du Wanxiang is the model of the elusive socialist woman that Ding had questioned and rejected for so long. A humble peasant, she becomes “liberated and powerful only when she serves the state and its people.” Further, she reaffirms archetypes such as the wise mother and good wife and replaces “the rebellious, restless, and inquisitive modern girl” with “the traditional feminine virtues that the socialist system reaffirmed.”

While this could be read as the defeat of Ding’s defiant spirit—an understandable result of years of exile and persecution—I interpret Ding’s shift as an expression of her commitment to the values of socialism at large, especially during a time where Maoism was being deconstructed by reformers. Ding spoke out against “spiritual pollution” from capitalist and Western forces in 1983, reaffirming her belief in Chinese socialism. Her novella speaks to Ding’s vision for socialist utopia and expresses her allegiance with correct Maoist thought.

Despite Ding’s entire literary career being riddled with contradictions and tensions between her ideologies and experiences, she was committed to her beliefs until the end. She was incisive and masterful in her portrayal of the female subject and all of her intricacies. Ding exemplified and narrated the complex relationship between socialism and feminism better than any of her contemporaries. Her feminism was nationalist, communist, anti-imperialist, and unapologetic. Through all of the attempts to mold Ding into the New Woman or perfect comrade that the Party wanted her to be, Ding spoke genuinely from a place of complexity and vulnerability. To her, the female subject was one that lusted, loved, dissented, and struggled. This model tore down the rigid confines of New Woman and Modern Girl and left in its place a space in the canon and in society for all women who followed her.